Resist News

They come to the U.S. to plea for help and safety with asylum only to be dumped in a cage and passed from prison cells to courtrooms and back by gruff and often hostile Americano guards and judges who may not speak their language. Their crime? Crossing the US-Mexico border seeking safety and security. The sentence? Being declared an “illegal alien” with no rights, no clear future. Tragically, most are eventually denied asylum and sent back, because they cannot prove “credible fear.”

I recently volunteered at the Karnes family immigration detention center in south Texas with women and children, working with RAICES, a pro bono legal services organization. We prepped the women for “credible fear” interviews and also wrote declarations with them to appear before an immigration judge. They were some of the bravest women I have ever known.

Karnes is set up like a high security prison where the women are treated like criminals along with their children, including babies. The guards often called the women and children by their Alien Registration Numbers (A#) or referred to them as “bodies.” All inmates, even 4- and 5-year-old children must wear their names and A#’s on a lanyard or string around their necks. We worked with many women, but not all request or have access to legal assistance. The names and former locations of the women I talked to have been changed to protect their privacy and for safety reasons.

Photo by Michael Crow, Arizona Republic

To stay in the US the women must prove that they have “credible fear,” when terror and anxiety had become a normal state for many at home and on their highly dangerous journey over several weeks or even months. Back home their sons and brothers and daughters may have been killed, disappeared, forced into gangs. But is that enough to prove “credible fear”? “I’m sorry but your fear isn’t sufficient to meet the legal standard of being credible,” so you aren’t granted asylum and we are sending you back. You didn’t talk in enough detail about your drunken husband beating you bloody every night while your children were forced to watch. It was your sister and not you who suffered the horror of being dragged behind the village school and raped again and again by 4, 5, 6 men from the local gang – she couldn’t keep count. They have threatened to do the same thing to you, but “your fear may not be credible.”

The Karnes Residential Center in Karnes, Texas is one of three family detention centers in the US, the second being the the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas, and the third in the Berks Facility Residential Center in Berks County, Pennsylvania. Karnes, which currently has 800 beds, has long been criticized by RAICES and other legal and human rights groups for its inhumane conditions including inedible food, lack of adequate medical care, sexual and other abuse of women and children. Children are often sick and most lose a significant amount of weight.

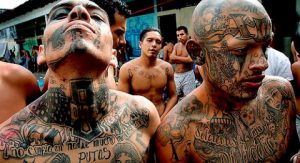

Gangs in Honduras by Cuentosarg.wordpress.com

In recent years, nearly 10% of the 30 million residents of the northern triangle of Central America –- meaning Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala — have fled from the violence, most for the United States. These countries have some of the highest homicide rates in the world, perpetrated by gangs, drug cartels and the hidden forces of repressive governments. Between October 1, 2015 and September 30, 2016, about 77, 674 families (mostly women and children) and 59,692 unaccompanied minors were apprehended by the Border Patrol, which is a massive increase over the year before (39,838 families and 39,970 unaccompanied minors). A vast majority of these desperate and terrified migrants are seeking asylum.

Many women have fled horrific domestic violence, which may qualify them for asylum:

Isobela was sobbing as she recalled that in 2014, her husband had told her he had “gotten involved with some bad people and that he loved us very much. He was so drunk that I didn’t pay much attention. Two days later I took my son to school and got a call that I should go directly home and there found all these fire trucks and police…my husband’s mother was screaming, ‘they killed him! They killed him!’ …so I went inside and saw he was dead with a bag over his head.” She saw that he had been strangled with a wire that almost decapitated him. Isobela later learned that her husband had worked for the narcos but never told her.

Then in December 2015 a man approached Isobela on the street and told her that her husband had owed him a lot of money, and if she didn’t pay, “the same thing that happened to your husband will happen to you and your son.” She recognized him as one of three brothers who were drug dealers in the local area in Honduras whom everyone called “Los Muertos.” Isobela began paying 2500 lempira/month (about $105 US) but then lost her job when the place where she worked went out of business. She was so terrified that she didn’t leave the house for a month, nor did she answer the phone until she could collect and borrow enough money to leave for the US.

To get asylum the women must prove “credible fear,” which is defined as “a ’significant possibility’ that [a woman] can establish in a hearing before an Immigration Judge that [she] has been persecuted or have a well-founded fear of persecution on account of [her] race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion if returned to your country,” according to USCIS (US Citizenship & Immigration Services). The “social group” may include leaders of teachers’ or labor unions, single mother heads-of-households, women business owners, LGBTs, women victims of extreme domestic abuse, women who themselves and/or their families are targeted by gangs, those who are poor, etc.. It may be that a family member, friend or co-worker is murdered or tortured by a gang and later gang member keep giving [the woman] threatening looks, but unless he says or does something directly to her that shows he intends to kill her, or abuses or assaults her, it may not qualify as credible fear.

Myrna talked about how she has suffered violence and abuse much of her life in Guatemala by her family and more recently by the father of her child. “He refused to admit that the baby was his when he was born, and has never given us any support,” she explained. Myrna never said the man’s name in my interview, only referring to him as “the father of my son.” Later she met and married her current husband, Erick, whose mother and brother were killed by M-18 Gang members. The father of her son has ties to that gang, which she knows because his chest and back were covered with M-18 tattoos. Back in 2009, Myrna’s grandfather and sister were massacred along with five other people in her grandfather’s house, because he had refused to pay extortion money to the gangs. The father of her son who was likely involved in the crime began persecuting and making death threats against Myrna because he believed she was a witness to the murder of her family members. After weeks of living in terror, Erick helped Myrna to find the money to flee to the U.S. with her 6-year-old son.

If a woman receives a negative decision from her credible fear interview with the asylum agent, she has the option to appeal by appearing before an immigration judge, presenting a very detailed declaration of her entire story. Many women are nervous, uncomfortable and possibly confused in their first interview and don’t mention certain violent or threatening incidents such as sexual assault, so the declaration often includes more details to make their claims of credible fear more convincing.

“I didn’t want to remember those terrible things,” said Jessica in explaining why she didn’t mention some of the violent incidents that she had experienced in her interview. But it was her son who talked about those when asked by the asylum agent, and said he was very afraid for both his mother and himself if they had to return home. The agent confronted Jessica so she told him the other stories, but it had affected her credibility and she was given a negative result. So Jessica asked to appear before an immigration judge, talking in greater detail about all that had happened.

If a woman receives a positive result from her first interview with the asylum agent, or her appearance before the immigration judge, she is released to go join family members or friends where they live in the US. If she is denied after both interviews, she needs to hire a lawyer to fight her case, although it’s likely she can’t afford it, and will be deported back to her home country. Many women said they were terrified of this possibility because they were sure they and their children would be killed.

Anita had been abused her entire life. When she was 13, her stepmother sold her to the landlord for food. He beat her and raped her for months. “He made me take some kind of pills, which I think were birth control pills.,,When I was 14, I met my husband and he seemed really nice, but when I went to live with him he drank a lot and beat me…I became pregnant and he choked me and I almost died.” Anita gave birth to her baby son but he died soon after. Anita’s husband became more abusive and she wanted to leave but had nowhere else to go. She later had another baby and decided to return to her father’s house, but he didn’t want her and her stepmother beat her and treated her like a domestic slave. Anita’s husband kept threatening to kill her and said that he had killed two of her cousins and she would be next. She couldn’t find work and had no food for her child, so she was finally able to borrow the money and leave the country. She is terrified to return to El Salvador because she knows her husband or family will kill her.

Extortion by gangs is all too common in El Salvador, as well as in Honduras and Guatemala. Gangs target the rich and the poor, often big and small business owners, demanding that they hand over a portion of their earnings, which may force them into bankruptcy. Those who refuse or can’t pay are killed. Unfortunately, these terrifying experiences may not qualify as “credible fear” for many of the women, and they are sent back.

Carla cried with fury and sadness as she recalled how hard she had worked for her dream to start her own small business selling food in a Guatemala City. But a month after it opened, five men arrived at her kiosk, pointed a gun at her head and said she must pay them 980 quetzales (about $130) every week or she and her 4-year-old daughter would be killed. She said she earned little more than that each week with her new business so couldn’t pay but they said she had no choice. She and her daughter lived alone, which made her more vulnerable to the gangs. Carla explained how she had called the police twice and each time they said they would investigate, but they never arrived. As a single mother and a woman with a small business who faces threats or has experienced violence, this may qualify as credible fear.

Another important criterion for “credible fear” is that the woman went to the police to report any incidents, but they couldn’t provide her with protection. In many Central American countries such as Honduras or El Salvador the police often don’t take action on complaints because they are connected with the gangs, usually the M-18 Gang or their rival gang, the Mara Salvatrucha or MS. People are also afraid to go to the police for fear of retaliation.

Cristina’s 11-year-old son Carlo was targeted at school in San Pedro Sula in Honduras and threatened with a knife by an older student who told him that if he didn’t carry drug money for the gangs, he and his mother would be killed. The gangs likely targeted Cristina and her son because she is a single mother and lived alone in her house with her son. “He didn’t want to go to school after that because he was afraid. I knew a private school would be safer for him but I couldn’t afford that.” She didn’t go to the police because “they never do anything anyway” and also feared the gang would find out and go after her and her son. She said that the police station near Carlo’s school closed for three days because the police were afraid of the gangs, so the neighborhood was left unprotected.

For many women in the immigration detention center the terror has long included the fear of the unknown. What will happen to my children? To me? To my sister? Will I be released and able to go live with my brother and his family in a place called Ohio? Or will I be sent back home where the gangs are waiting to drag my 11-year-old son into their ranks to carry drug money? Will I be forced to remain in this cold and sterile limbo, living in a high security facility owned by GEO – the private company that owns the prison, eating food that makes my children sick? My little daughter can’t stop coughing from our trip north that took a month and it was so hard. The worst was to see my children so cold and hungry and I couldn’t do anything for them. And the rules in this place keep changing, every week, every month and no one knows why.

Photo: Adjunct Justice

When women and children cross the US-Mexico border and are apprehended by the Border Control, they are separated from any children who are older than 17 or husbands and often have little idea of their legal rights. They face inhuman and appalling conditions by first being taken to what is commonly known by both immigrants and guards as “la hielera” (the freezer), which is a cement building with concrete floors and benches with frigid temperatures. The women told me that there are no mattresses or pillows and they may be packed into a cell so crowded that many don’t have space to lie down. Everyone sleeps on the floor including the children, with just a thin aluminum blanket for warmth. Their fingers and lips may turn blue. For those who enter the US into Texas by crossing over the Rio Grande River, many are still wet but are often kept in these ice-cold cells for 1-6 days and nights, and many become ill.

One woman described how there was no privacy, and the toilet was behind a short wall in the corner, and toiletries and soap were in short supply. The lights are generally kept on for 24 hours a day, and the guards often harass and ridicule them. One woman told me that “they yelled at us and said we didn’t deserve to be here, that we were illegals and should stay home!”

Photo: Mother Jones

After this ordeal in la hielera, the migrants are then taken to “la perrera” (dog kennel) where they are put into large chain link cages in warehouses. The women said that they and their children slept on foam mattresses on the floor and were given three sandwiches a day.

Tania said that she was so relieved to arrive at la perrera after a brutal one-month journey with her son. “I couldn’t stand to see my son so cold and hungry.” She said she finally felt safe and dry with food to eat. At one point on their journey, she and her son were kidnapped and the perpetrators called her husband back in El Salvador and demanded money to let her go. He could only pay part of it but they released her and her son, but she was sure she wouldn’t make it.

From la perrera where they stay for 1-3 nights, the migrant women are transferred to a family immigration detention center such as Karnes, often run as a for-profit facility by GEO or CCA (Corrections Corporation of America), as a high security facility for women and children. Along with inhumane conditions, the rules in the detention facility are often changing without notice and for no stated reason.

In the waiting area in Karnes, migrant children are restricted to playing with toys on a 9 x 5 foot rug while their mothers meet with pro bono lawyers in private visiting rooms. Many of the children I saw were obviously traumatized with haunted looks in their eyes, and some were afraid to be away from their mothers. I witnessed one of the women guards in the waiting room yelling at 4 and 5-year old children for violating the rules, such as taking a toy out of the play area. Women whose children began to cry or argue with other kids quickly rushed to get them to stay quiet and behave for fear of retaliation.

In November, GEO announced that the kids were banned from using crayons. The reason? The children accidentally colored on a table top, which “caused damage to the contractor” with “destruction of property,” so no more crayons.

Many of the women and children are on “expedited release” and must remain locked up for their credible fear interviews to learn if they can be released to their families in the US. Those who are able to leave will need to hire a lawyer and follow a long process to seek asylum over months or a year or more. Unfortunately, many do not get asylum because they must provide documents, affidavits or other concrete evidence of persecution, which many do not have. Many women do not report assaults or threats by gangs to police because they are afraid of retaliation, so don’t have a written police report as evidence. They may have fled after witnessing the murder of a husband or family member, but many cannot prove it.

Even if the women at Karnes don’t get asylum, telling their stories to a sympathetic listener seemed to serve as a brief catharsis for many women. “Thank you for listening,” many commented as they left to return to their cells. These women were the bravest people I had ever met. Many of them had heard about the dangers of the hard and brutal journey to the US and the fact that they may be locked up before being able to join their families, but they had decided to try anyway because they felt it was their only option to protect themselves and their children from the threats and violence back home.