April 20, 2012

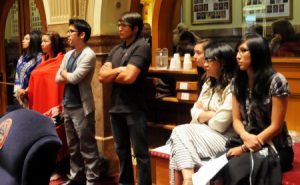

The group of young American Indians stood at the back of the Colorado State Senate Chambers, listening intently as several legislators refused to vote for a resolution that acknowledged the brutal history of indigenous peoples in the United States as a form of genocide.

American Indian youth observe debate on Colorado Senate resolution; from right to left: Amanda Williams, 18, Jessica Pearl Salas, 21, Miyeko Inafuku, 22, Lance Tsosie, 22, Simon Moya-Smith, 28, Tessa McLean, 21; and Olga Gonzalez. (Photo by Margie Thompson)

The day before, the Senate unanimously passed a resolution on the Holocaust as genocide, and that morning they did the same to recognize the Armenian genocide. But they refused to give the same recognition to the American Indians with Senate Joint Resolution 12-046, arguing that there were “wrongful acts” by the US government taken against Native Americans but insisted it was not genocide.

After considerable debate, the Senators passed the resolution (24-9, 2 absent), substituting “atrocities” for the word “genocide.” The measure also designates November, 2012 as First Nation Appreciation Month in Colorado.

Colorado State Senator Suzanne Williams (D-Aurora)

Sen. Suzanne Williams (D-Aurora), a Comanche and only Native American member of the state legislature, was the primary sponsor of the resolution. She fought valiantly to resist the word change, but in the end capitulated in order to get it passed. She called it an important step toward passing another stronger resolution next year.

But the American Indian students were devastated. “Our resolution died,” declared Simon Moya-Smith an Oglala Lakota who is a journalist, graduate student in the Dept. of Media, Film & Journalism Studies at the University of Denver, and member of that school’s Native Student Alliance (NSA).

“This is about their version of history, not our history…removing the word genocide changes the voice and purpose of the resolution,” said Moya-Smith. He noted that it was another example of the widespread disrespect and ignorance about the bloody and brutal treatment of First Nations peoples by European settlers.

“What purpose does it serve?” asked Olga Gonzalez as she watched the resolution pass without the original “genocide” term. “It doesn’t even serve their children.”

“It’s like a punch in the stomach,” said Amanda Williams, the tears flowing down her face. “For so many people on the reservations, it’s like a slap in the face,” said Williams, a member of the Navajo and San Carlos Apache tribes, and a leader of the NSA as a student at DU.

“Did you see how [the legislators] wouldn’t even look at us [as they walked in and out of the chambers]?” said Tessa McLean, Anishanaabe/Ojibwe, a youth leader in the American Indian Movement (AIM) and student at the University of Colorado-Denver.

The young Natives listened earlier that morning as Sen. Lois Tochtrop (R-Thornton) presented the Armenian genocide resolution. She stood in front of her colleagues sobbing about the brutalities committed against Armenians by the Ottoman Empire (later Turkey) in 1915.

“You wouldn’t believe the atrocities,” she said, describing how people were dragged from their homes, their belongings all burned and destroyed, and the women were raped and forced into sexual slavery while many others were deported. “We can never, never forget,” declared Tochtrop.

The parallels were all too obvious with the attacks and slaughter of American Indians as a result of government policies based on the belief in Manifest Destiny.* U.S. Presidents ranging from George Washington and Thomas Jefferson to Teddy Roosevelt called on military troops to force Indians off their lands or even kill them to enable further Western expansion by non-Indians.

Pres. Roosevelt once said, “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of ten are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.”

The near annihilation of American Indians from an estimated 18 million before the conquistadors arrived in the late 15th century to about 1.7 million people today is the result of a brutal history, mostly at the hands of the US government and European settlers. As stated in the resolution, “Many American Indian deaths were caused intentionally or because of disease, which was intensified by volitional acts of cruelty, such as forced migrations, deprivation of nutrition, and enslavement.”

Tessa McLean said, “My traditional homeland territory [in Canada] was invaded by the French, English, Ukrainians and Germans; they came to control our waters, take our land and our women. These invaders came to trade, in the process, they stole our culture to build their own wealth.” Her statement was read to the full Senate by Sen. Irene Aguilar (D-Denver). McLean, continued, “My people were placed on small reservations, our children were sent to residential schools, our traditions were lost, our ceremonies lost and our language was almost forgotten. ”

The resolution cites examples of brutality including the Trail of Tears in 1838-1839, in which 28,000 people of the Cherokee Nation were evicted from their ancestral lands in Georgia and forced to march 1,200 miles during a severe winter, resulting approximately 4,000 deaths. Also mentioned is the brutal attack in 1864 by Colorado Territory militia on 800 American Indians in Sand Creek, Colorado, massacring 150-200 mainly elderly women, men and children. Williams said that these are the better known examples of countless others.

But the Republican legislators who opposed the resolution refused to believe that the US government had imposed deliberate policies of displacement and extermination.

Sen. Ellen Roberts (R-Durango) was the first to raise questions about the word “genocide,” noting that when she looked up the definition, it said “the deliberate and systematic elimination of a national, racial, political or cultural group.” She said she works with indigenous law and many American Indians in her district, and “thank God that we have not destroyed totally the Native American people.” But with this definition, the Holocaust and Armenian massacres would not qualify as “genocide” either.

“We don’t deny there were some ‘wrongful actions,’ ” said Sen. Ted Lundberg (R-Loveland) who introduced himself as an historian, but to refer to these as genocide is “historical revisionism, not historical accuracy.”

“To call it genocide is doing a disservice to those who were victims of the Holocaust and other genocides,” declared Sen. Ted Harvey (R-Douglas County). Harvey also complained about the Native American students being in the Senate Chambers to pass their comments along to Sen. Williams during the debate about the resolution.

“It’s ignorance,” said Rose McGuire, a Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate who is the Indian Education Program Manager with Denver Public Schools, who also observed the debate on the resolution. “We have no history as far as the schools are concerned,” referring to how little many people know about American Indian history, including these legislators. “We are invisible.”

END

*Manifest Destiny is “the belief or doctrine, held chiefly in the middle and latter part of the 19th century, that it was the destiny of the [Anglo-Saxon] U.S. to expand its territory over the whole of North America and to extend and enhance its political, social, and economic influences” (Dictionary.com). Many scholars and activists contend that this same doctrine is evident with the US government today in aggressive actions to “spread democracy and freedom” throughout the world.

For more information contact the author at: [email protected].