Women protest against the expansion of the anti-abortion law with signs that say “The criminalization of abortion is State violence against women” and “The ARENA proposal for 30-50 years in prison [for abortion] condemns women to death”

By Kathy Bougher, ESCRIBANA correspondent

Under El Salvador’s current law, when women are accused of abortion, prosecutors can—but do not always—increase the charges to aggravated homicide, thereby increasing their prison sentence. This new bill, advocates say, would heighten the likelihood that those charged with abortion will spend decades behind bars.

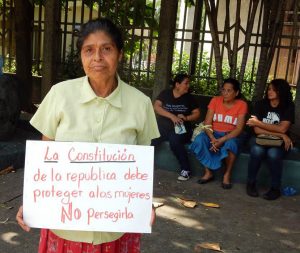

“The constitution of the Republic should protect, not persecute women”

The bill’s major sponsor, Rep. Ricardo Andrés Velásquez Parker, explained in a television interview on July 11 that this was simply an administrative matter and “shouldn’t need any further discussion.”

Abortion has been illegal under all circumstances in El Salvador since 1997, with a penalty of two to eight years in prison. Now, the right-wing ARENA Party has introduced a bill that would increase that penalty to a prison sentence of 30 to 50 years—the same as aggravated homicide.

The bill also lengthens the prison time for physicians who perform abortions to 30 to 50 years and establishes jail terms—of one to three years and six months to two years, respectively—for persons who sell or publicize abortion-causing substances.

The bill’s major sponsor, Rep. Ricardo Andrés Velásquez Parker, explained in a television interview on July 11 that this was simply an administrative matter and “shouldn’t need any further discussion.”

Since the Salvadoran Constitution recognizes “the human being from the moment of conception,” he said, it “is necessary to align the Criminal Code with this principle, and substitute the current penalty for abortion, which is two to eight years in prison, with that of aggravated homicide.”

The bill has yet to be discussed in the Salvadoran legislature; if it were to pass, it would still have to go to the president for his signature. It could also be referred to committee, and potentially left to die.

Under El Salvador’s current law, when women are accused of abortion, prosecutors can—but do not always—increase the charges to aggravated homicide, thereby increasing their prison sentence. This new bill, advocates say, would worsen the criminalization of women, continue to take away options, and heighten the likelihood that those charged with abortion will spend decades behind bars.

In recent years, local feminist groups have drawn attention to “Las 17 and More,” a group of Salvadoran women who have been incarcerated with prison terms of up to 40 years after obstetrical emergencies. In 2014, the Agrupación Ciudadana por la Despenalización del Aborto (Citizen Group for the Decriminalization of Abortion) submitted requests for pardons for 17 of the women. Each case wound its way through the legislature and other branches of government; in the end, only one woman received a pardon. Earlier this year, however, a May 2016 court decision overturned the conviction of another one of the women, Maria Teresa Rivera, vacating her 40-year sentence.

Velásquez Parker noted in his July 11 interview that he had not reviewed any of those cases. To do so was not “within his purview” and those cases have been “subjective and philosophical,” he claimed. “I am dealing with Salvadoran constitutional law.”

During a protest outside of the legislature last Thursday, Morena Herrera, president of the Agrupación, addressed Velásquez Parker directly, saying that his bill demonstrated an ignorance of the realities faced by women and girls in El Salvador and demanding its revocation.

“How is it possible that you do not know that last week the United Nations presented a report that shows that in our country a girl or an adolescent gives birth every 20 minutes? You should be obligated to know this. You get paid to know about this,” Herrera told him. Herrera was referring to the United Nations Population Fund and the Salvadoran Ministry of Health’s report, “Map of Pregnancies Among Girls and Adolescents in El Salvador 2015,” which also revealed that 30 percent of all births in the country were by girls ages 10 to 19.

“You say that you know nothing about women unjustly incarcerated, yet we presented to this legislature a group of requests for pardons. With what you earn, you as legislators were obligated to read and know about those,” Herrera continued, speaking about Las 17. “We are not going to discuss this proposal that you have. It is undiscussable. We demand that the ARENA party withdraw this proposed legislation.”

As part of its campaign of resistance to the proposed law, the Agrupación produced and distributed numerous videos with messages such as “They Don’t Represent Me,” which shows the names and faces of the 21 legislators who signed on to the ARENA proposal. Another video, subtitled in English, asks, “30 to 50 Years in Prison?“

International groups have also joined in resisting the bill. In a pronouncement shared with legislators, the Agrupación, and the public, the Latin American and Caribbean Committee for the Defense of the Rights of Women (CLADEM) reminded the Salvadoran government of it international commitments and obligations:

[The] United Nations has recognized on repeated occasions that the total criminalization of abortion is a form of torture, that abortion is a human right when carried out with certain assumptions, and it also recommends completely decriminalizing abortion in our region.

The United Nations Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights reiterated to the Salvadoran government its concern about the persistence of the total prohibition on abortion … [and] expressly requested that it revise its legislation.

The Committee established in March 2016 that the criminalization of abortion and any obstacles to access to abortion are discriminatory and constitute violations of women’s right to health. Given that El Salvador has ratified [the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights], the country has an obligation to comply with its provisions.

Amnesty International, meanwhile, described the proposal as “scandalous.” Erika Guevara-Rosas, Amnesty International’s Americas director, emphasized in a statement on the organization’s website, “Parliamentarians in El Salvador are playing a very dangerous game with the lives of millions of women. Banning life-saving abortions in all circumstances is atrocious but seeking to raise jail terms for women who seek an abortion or those who provide support is simply despicable.”

“Instead of continuing to criminalize women, authorities in El Salvador must repeal the outdated anti-abortion law once and for all,” Guevara-Rosas continued.

In the United States, Rep. Norma J. Torres (D-CA) and Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL) issued a press release on July 19 condemning the proposal in El Salvador. Rep. Torres wrote, “It is terrifying to consider that, if this law passed, a Salvadoran woman who has a miscarriage could go to prison for decades or a woman who is raped and decides to undergo an abortion could be jailed for longer than the man who raped her.”

ARENA’s bill follows a campaign from May orchestrated by the right-wing Fundación Sí a la Vida (Right to Life Foundation) of El Salvador, “El Derecho a la Vida No Se Debate,” or “The Right to Life Is Not Up for Debate,” featuring misleading photos of fetuses and promoting adoption as an alternative to abortion.

“The healthy and lives of women are well worth the debate”

The Agrupacion countered with a series of ads and vignettes that have also been applied to the fight against the bill, “The Health and Life of Women Are Well Worth a Debate.”

Mariana Moisa, media coordinator for the Agrupación, told Rewire that the widespread reaction to Velásquez Parker’s proposal indicates some shift in public perception around reproductive rights in the country.

“The public image around abortion is changing. These kinds of ideas and proposals don’t go through the system as easily as they once did. It used to be that a person in power made a couple of phone calls and poof—it was taken care of. Now, people see that Velásquez Parker’s insistence that his proposal doesn’t need any debate is undemocratic. People know that women are in prison because of these laws, and the public is asking more questions,” Moisa said.

At this point, it’s not certain whether ARENA, in coalition with other parties, has the votes to pass the bill, but it is clearly within the realm of possibility. As Sara Garcia, coordinator of the Agrupación, told Rewire, “We know this misogynist proposal has generated serious anger and indignation, and we are working with other groups to pressure the legislature. More and more groups are participating with declarations, images, and videos and a clear call to withdraw the proposal. Stopping this proposed law is what is most important at this point. Then we also have to expose what happens in El Salvador with the criminalization of women.”

Even though there has been extensive exposure of what activists see as the grave problems with such a law, Garcia said, “The risk is still very real that it could pass.”

See more of Kathy’s photos of the protests by women in El Salvodor.

This article was originally published in ReWire.